New Media

Readings:

- Mass Media and American Politics (by Johanna Dunaway and Doris. A. Graber)

- Chapter 13: Media Effects: Then and Now

Internet, in particular the World-Wide-Web, was developed during the 1990s. It became clear at that early stage that the new digital technology had a revolutionary potential. As a matter of fact, we can talk today about Internet as we do when we discuss the invention of the printing press or the rise of TV.

The difference with those revolutions in the past is that the new communication technologies impact not only mass communication, but all possible communication contexts. New digital media, particularly social media, are used as channels for interpersonal and small group communication, for professional and mass communication. People use those platforms to contact friends of the elementary school or to search for their adolescence love. The same social networks are used not only to plan social activities, but to develop those activities in the very same platforms, mostly through challenges or avalanche-like imitation processes. Particularly in these worrying times brought about by the Covid-19, the social networks have become an indispensable tool to work remotely. And finally, some platforms, such as Twitter allow users to reach a mass audience that was unthinkable a couple of years ago even for the most powerful TV networks.

Of course, in the area of political communication, they have become the most effective, direct and immediate way to communicate with their audiences and react to urgent issues. We cannot understand contemporary politics without the aid of digital technologies to articulate grassroots actions or finance political campaigns.

In this learning unit, we explore which the revolutionary features of digital communication are, and furthermore how Internet has changed the media landscape, its impact on traditional media, and the new rules in the political game.

The Digital Revolution

Wil discuss in this section what the term “digital” means. Even though the use of the word is broadly spread, the definition is not always clear. It is also relevant to understand the difference between the traditional “analogue” media and the new digital ones.

“Analogue” media contents are store in an object, meaning physical phenomena are coded and transformed into another physical object. “Analogue” contents must be coded and decoded using technological devices. For instance, the film camera and the film projector, or the microphone and the recording studio and the record player. In between these two devices, a product is created: the “analogue” media product. It can the record, the film, the tape or the DVD. In some cases, we do not need any device to decode the “analogue” content, but just a cultural process. This is the case, for instance, of the book. We do not need any device to read a book, but a cultural process, what we call “reading”.

Digital processes imply that input data are not code into another “analogue” artifact/object, but into numbers. This is the meaning of the word “digit”, number, that derivates from Latin “digitus”. This word means “finger”. It is no surprise that the word for number is originally the same word as the word for finger, or the our numerical decimal system is based on the magic number 10.

In any event, the transformation of “analogue” to “digital” means that a system of symbols (abstract numbers) replace physical objects. Many believe that “digital” is a synonym of “binary”. This is not accurate, even if the computer revolution is in fact based on a binary system. “Digital” is simply the assignation of numeric values to real phenomena. It could have been a decimal system (0 to 9), which would identify 10 different values. The reason why the binary system, which only has two values (1 and 0), was adopted is that it make it easier and faster for computers to complete the calculations.

The consequences of the technological shift – “analogue” to “digital” – have a revolutionary potential:

- The process becomes more abstract, as it gets rid of physical objects (numbers replace physical objects).

- The storage is simplified. We can keep our whole library, all our music and videos and our computer at home. Imagine the amount of space that saves.

- We can access this information easily and rapidly from any place – even with our cell phones.

- I can be also easily and rapidly manipulated. We can now edit a whole film in our computer. Let alone the alterations Photoshop makes possible.

When it comes to mass communication, there are two novelties that might change mass media in a radical way.

1 Interactivity

Mass communication is canonically defined by the technological infrastructure necessary to create and distribute messages to a large, anonymous and passive audience. It is passive since the input potential of the audience, its ability to send any type of feedback, is rather limited. That changes with digital communication technologies.

The interactivity is one of the revolutionary features of Internet.

First, the users have the potential to interact with the text. This is what the term “hypertextual navigation” refers to. Through hyperlinks we, users, can move from one point to another within or outside the text.

Then, most of the internet Web-sites, portals or platforms allow the users to express their opinions about their contents. They can express those opinions, as well as their assessments the contents.

Finally, there a plethora of online platforms in which the users generate the contents. This is the case, for instance, of Wikipedia and other online encyclopedias. The explosion of social media makes this type of interactivity even more radical. Then contents of every single account is generated by the user. In most cases, that personal information is the only content of the whole platform. YouTube does not produce any video. It is only a platform where the users can publish their own videos.

2 Networked Media

A powerful technological infrastructure is one of the characteristics of mediated mass communication. This, of course, creates an unbalance between the sender and the receiver of messages. Only those who have access to that technological infrastructure may become senders. And to have access to that infrastructure, a significant amount of capital is indispensable. The mass audience must be satisfied with the role of passive receivers of information.

The studio (film, radio or TV studio) or the newsroom in the case of the press can be considered the heart of the traditional mass media. Thus, the production of media contents was heavily centralized.

This changes with the irruption of digital technologies. The computer server is at the heart of the new system. The server is not a centralized location of information, but only a “node” in a network of interconnected computers. Every computer connected to the network, all our PCs and cell phones, can upload and retrieve information from the system. That makes possible that the user becomes, at the same time, consumer and producer of contents.

As a consumer, you can buy a $ 2,000 digital camera that allows you to create high-definition movies that can be distributed in movie theaters and DVDs. The PC itself becomes the ultimate tool for consuming and producing media contents. With a PC you can consume information, but can also produce and distribute it. You can use it to edit movies, mix music, or publish Web-sites. And you can do it for just a couple of hundreds of dollars.

Convergence

The process of convergence has been the response of the established mass communication companies to face the challenge brought about by the digital revolution. Even if the phenomenon of convergence is multidimensional – we can talk about cultural and technological convergence as well – we will focus in this course on the economic convergence. And we will do that because this of the implications of this type of convergence for the political discourse.

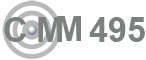

The word “oligopoly” derivates Greek ὀλίγοι (olígoi, “few”) and πωλέω (pōléō, “to sell”). It describes a system where only a few have the control of the means of production and distribution of a particular good or service (the monopoly would be the system where only ONE actor owns the market). The word perfectly fits the media market that results from the process of convergence: An economic structure in which a few, very large, very powerful, and very rich owners control an industry or series of related industries. The result of media economic convergence is, logically, a more centralized structure happening at the time of decentralization. The result of the convergence process is the consolidation of large companies merging with each other or absorbing other companies, forming even bigger companies (see the map of the 6 largest media companies).

(Source: WebFX)

This oligopolistic model has serious implications for the political discourse. The plurality of voices is essential in a democratic system. If the number of sources is so dramatically reduced (only 6 companies in a country of close 350 million people), we can assume, first, that the spectrum of political ideas may be limited, and the freedom of expression compromised. And then, we must also wonder to what extend such powerful companies might influence political actors and organizations.

In the next graphic, you can see how the distributions of contents generation in the media map:

It is doubtful, though, that this media business model will success. As a matter of fact, The use of traditional mass media is in clear decline, above all by the younger generations.

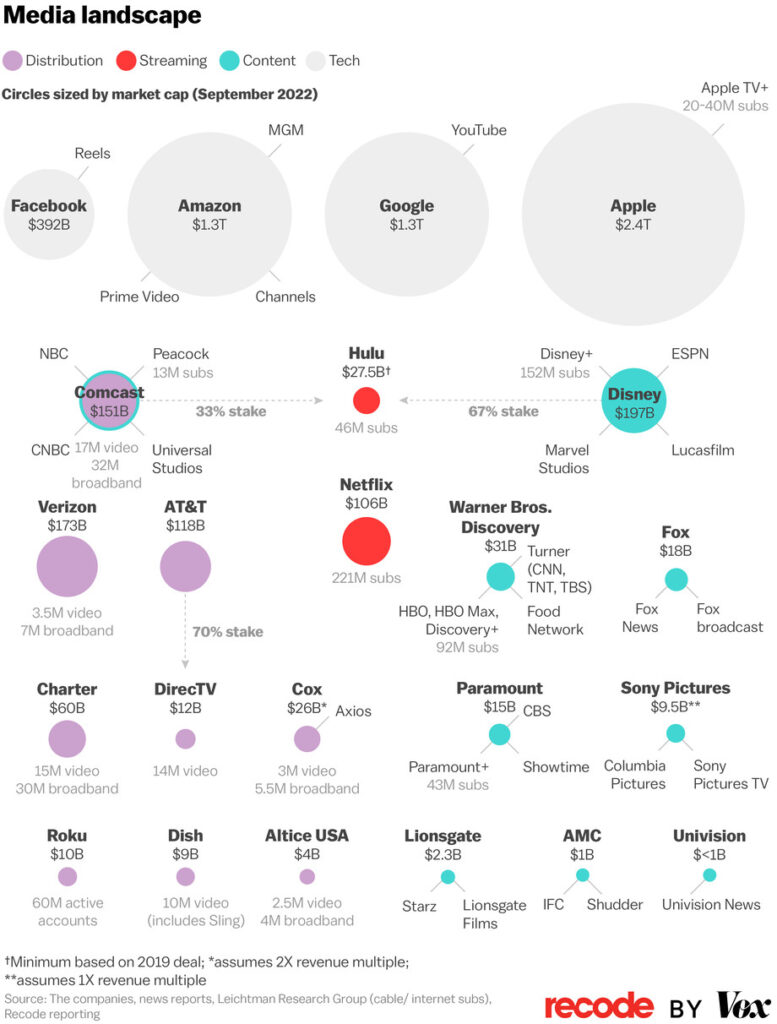

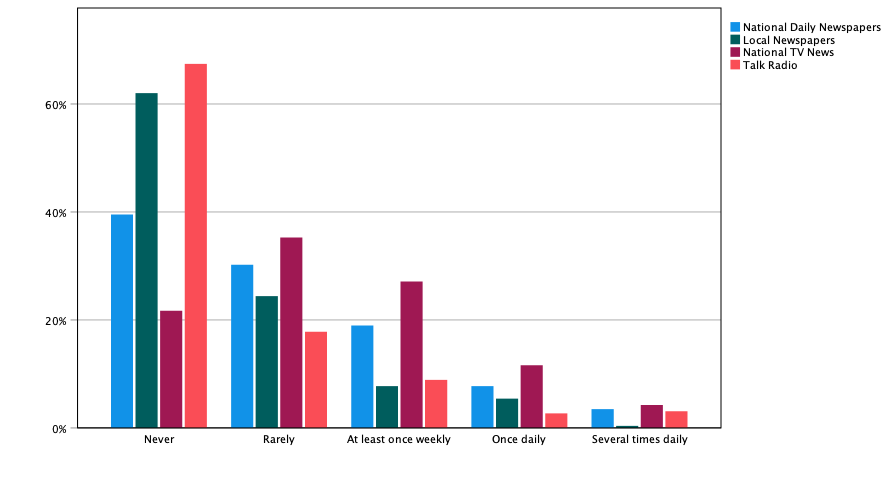

The study of media consumption habits among college students in the state of Connecticut confirms this trend. In a study of 258 students enrolled in program in all the public institutions of higher education in CT (the four universities of the state system, the University of Connecticut and the 12 community colleges), the vast majority of students stated that they never or rarely read national and regional newspapers or listens to radio shows. The number of students who watch TV is higher, although, again, just 15% do it daily.

Most of the participants in this study, when looking for news, resort to online video platforms (such as YouTube), or rely almost entirely on social media.

The question mass communication researchers are asking themselves is:

How can media companies survive if the users vanish?

The situation is particularly serious for the print media. Newspapers, even in their online editions, are losing readers. The traditional source of revenues for newspapers and magazines, in addition to subscriptions, has been for over a century advertising. Still, in order to persuade advertisers to buy space in your pages is to show them the solidity of your readership. The escape of readers is causing massive problems for newspapers at local, regional or national level. They are firing staff that was essential to secure the quality of the information and the quality of the writing. The economic incentives that may have attracted young vocational journalists in the past has likewise disappeared. Who would nowadays want to become a journalist being aware that it may take years to get the first decent salary?

This is a global phenomenon, at least the in the Western world. We can observe the same development in most European countries. The traditional media, not only the print, are now surviving thanks to institutional advertising. Government agencies at local, state or nation level are financing those media outlets that theoretically should be surveilling them.

The situation in the U.S. is different since the involvement of the state is not that evident. The rescue, in this case, comes form individual fortunes. Carlos Slim, the Mexican billionaire, became the top shareholder of the New York Times in 2015. Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon and one of the richest individuals of the globe, bought The Washington Post in 2013. The open question is why those successful businessmen decided to invest vast amounts of money in companies that had a more than bleak future.

Impact of Social Media

The decentralization of mass communication – this is one of the characteristics of digital networked media – triggered a wave of optimism. Many media theorists and scholars thought that this could enhance political diversity giving more weight to independent voices, political standpoints that did not belong to the mainstream.

The original optimism was very soon curbed. The selective exposure also works in social networks. They work as echo-chambers, where the own ideas mostly produce reverberation, and seldom opposition.

Newsfeeds may introduce some variety since, as opposed to what happens with the Web-site of newspapers and magazines, they are not limited to only one source. Still, this potential diversity of sources is limited because in most cases, newsfeeds respond to algorithms that based the selection on the users’ browsing history.

People share in social media pieces of information they found interesting, or they thought their friends, followers or contacts may find interesting as well. There is some empirical evidence that Facebook might influence attitudes or even behaviors of their users (source). In this sense, social networks function similarly to the way traditional networks do. We learn through Paul Lazarsfeld that influence follows a multi-step flow. Opinion leaders seem to play an essential role also in social media.

Political candidates are very well aware of the potential of those informal digital social networks. Barrack Obama was one of the pioneers – also – in the systematic use of social networks in electoral campaigns. Barack Obama made extensive use of Internet to raise money in 2008. Supporters could go anytime to BarrackObama.com where they could find means to give money for Obama. In his Web-site, the candidate also informed about his intensive online presence. The results of the campaign were impressive. Obama raised through the Internet $116,457,694. Still, the real break-through happened in the 2012 electoral campaign, when his team developed micro-targeting strategies based on exhaustive data mining. Through Obama’s Facebook application, his supporters were given them permission to access the information stored in their Facebook accounts, pictures, newsfeed and – most importantly the list of their Facebook friends. The tricky aspect of this strategy is that, even if the users agreed on the terms, their friends did not.

Years later, Donald Trump hired Cambridge Analytica to develop a similar data driven strategy. This company created, using the information retrieved from Facebook, to create sophisticated psychological profiles. Specially interesting is in this case the different treatment both cases were given by the press. While in Obama’s case it was presented as a proof of his genius, the second case was framed as “the Cambridge Analytica scandal”. In spite of the ethical concerns this practice may raise, there is no empirical evidence that it was really effective to change the vote of the targeted people. (Read more about this case in this link).

Social Media and Grassroots Actions

The explicit idea behind grassroots actions is to use public opinion, the power that flows from opinion, to exert pressure on legislators. Grassroots actions allow us to articulate the opinion of those groups of individuals who do not have access to the media outlets. The premise is that letters and phone calls from private citizens are more influential than arguments from vested interests. The greatest benefit of grassroots politics is that there are virtually no rules or regulations.

Still, grassroots may have a more subtle aim. We learned with Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann (learning module on public opinion) that those opinions that are not expressed in public tend to disappear. This fact is especially relevant in political communication. Political parties and candidates are constantly trying to avoid “spirals of silence” against their positions. To this aim, grassroots actions are a powerful tool in political communication.

Stealth Grassroots

It is tempting to abuse the power that flows from public opinion. There have been attempts to generate this kind of pressure manipulating the people.

This is what is called stealth lobbying which happen when grassroots actions are created under the cover of front groups. The public is not told what the vested interests are behind a particular campaign.

An example of this unethical practice is the case of Freddie Mac. This company was accused of hiring DCI a firm to create a stealth lobbying campaign to kill legislation that would have regulated and trimmed the mortgage finance giant and its sister company, Fannie Mae, three years before the government took control to prevent their collapse. (Source)

Social Media and Political Activism

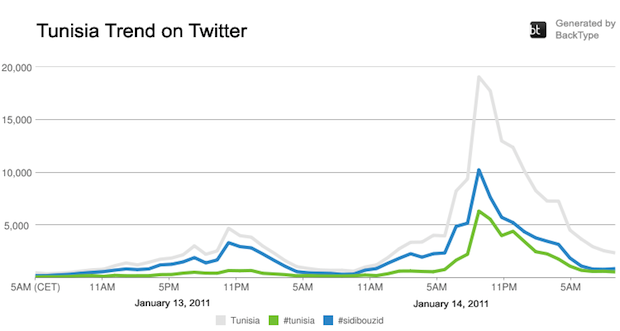

Social media open a new frontier for political activism. The potential became clear during the so-called Arab Spring in the early 2010s. The protest originated in Tunisia on December 17th, 2010, where a man named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in the remote region of Sidi Bouzid, in the center of the country. The actual reason was that he was denied a permit to work as a street vendor. The incident sparked a massive popular reaction. Twitter became the most effective tool for the protesters to communicate to each other and organize the subversive actions. As a matter of fact, the unrests became known as “the Twitter Revolution”. The graphic shows the activity in Twitter during the first weeks of 2011:

The protests were successful. Dictator Ben Ali resigned and escaped from the country on January 14th. Few weeks later, in February 2011, a very similar movement developed and Egypt. Social Media, Twitter and Facebook mostly, also became instrumental for the activists. Even if the government try to stop the spread of communication shutting down Internet, the pacific revolution triumphed with the same outcome: Egypt’s president Hosni Mubarak resigned on February 11.

In recent years, social movements like Global Social Justice or Black Live Matters rely almost entirely on Social Media to articulate public opinion dynamics. Social media are perfect platforms for fast mobilization of grassroots actions (sit-in protests, marches, rallies, riots, or any type of boycotts). They require less infrastructure and money, and do not imply any formal membership. Plus, the activity in social media is also an excellent platform to provide the media with the information they need to cover – or give free publicity – to all their actions.